On May 1, 1981, Dr. Clarence A. Bacote, a pioneering African American historian and political scientist, passed away in Atlanta at the age of 75. A professor at Atlanta University for over four decades, Bacote was instrumental in documenting African American political engagement in the South. His seminal work, The Negro in Georgia Politics, 1880–1908, remains a foundational text in Black political history. Beyond the classroom, Bacote was active in the civil rights movement, promoting voter registration and civic participation. His scholarship and advocacy helped bridge the gap between historical research and political activism.

On May 1, 1950, poet Gwendolyn Brooks made history as the first African American to win a Pulitzer Prize. She received the prestigious award in poetry for her book Annie Allen, a groundbreaking collection that chronicles the life of a young Black girl coming of age in Chicago. Brooks’ powerful command of language and exploration of Black identity, motherhood, and urban life elevated her voice to national prominence. Her win marked a milestone for African American literature and helped open doors for future generations of Black writers.

Born May 1, 1930, in St. Louis, Missouri, Grace Bumbry broke numerous racial barriers in the world of opera. Trained in both Europe and the U.S., she rose to international fame after performing at the Bayreuth Festival in 1961—a prestigious venue historically closed to Black artists. Her performance as Venus in Tannhäuser was a sensation, earning her a 30-minute ovation. Bumbry became one of the first Black opera stars to gain global recognition and later helped pave the way for other African American classical performers. She also established a foundation to mentor young opera singers.

Throughout her illustrious career, Bumbry performed at major opera houses worldwide, including the Royal Opera House in London, La Scala in Milan, and the Metropolitan Opera in New York. Her repertoire encompassed both mezzo-soprano and soprano roles, showcasing her vocal versatility. Notable performances include Amneris in Verdi’s “Aida,” Carmen in Bizet’s “Carmen,” and the title role in Puccini’s “Tosca.” ?Wikipedia

Bumbry’s contributions to the arts were recognized with numerous accolades. In 1972, she received a Grammy Award for Best Opera Recording. She was also named Commandeur des Arts et des Lettres by the French government and was honored with the Kennedy Center Honors in 2009 for her influence on American culture through the performing arts. ?Wikipedia

Grace Bumbry passed away on May 7, 2023, in Vienna, Austria, at the age of 86. Her legacy endures as a groundbreaking artist who not only captivated audiences with her performances but also paved the way for future generations of African-American opera singers.

Though not African American, Judy Collins, born May 1, 1941, played an important supporting role in the Civil Rights Movement through her music. As a folk singer during the 1960s, she performed at numerous civil rights events and marches, lending her voice to causes of racial justice. Collins collaborated with Black artists and sang spirituals and freedom songs, using her platform to elevate the movement’s message. She remains a notable example of multiracial solidarity in the fight for civil rights.

On May 1, 1969, Fred Hampton, the charismatic leader of the Illinois Black Panther Party, gave a passionate speech at the University of Illinois, calling for racial and class solidarity. Hampton was known for his revolutionary message of unity between poor whites, Latinos, and Blacks, coining the term “Rainbow Coalition.” His oratory on that day resonated with students and activists across racial lines, challenging the government’s narrative of the Panthers as a purely militant group. His speeches, including this one, made him a target for FBI surveillance, ultimately leading to his assassination later that year.

On May 1, 1866, just after the Civil War, Fisk University was founded in Nashville, Tennessee by the American Missionary Association. Created to provide education to newly freed African Americans, Fisk quickly became a beacon of Black academic excellence. Despite meager resources, the university emphasized classical education, the arts, and activism. Its world-famous Jubilee Singers later raised funds globally, helping save the institution from closure. Fisk has produced notable alumni like civil rights activist W.E.B. Du Bois and U.S. Representative John Lewis. It stands today as a Historically Black College and University (HBCU) with deep roots in freedom, resilience, and Black intellectual tradition.

On May 1, 1967, the United States entered what would become one of the most explosive summers of civil unrest in the nation’s history. Between May 1 and October 1, over 40 major race-related riots and more than 100 smaller disturbances erupted across the country. Fueled by long-standing grievances over police brutality, housing discrimination, unemployment, and systemic racism, these uprisings became known as part of the “Long, Hot Summer of 1967.” Cities such as Detroit, Newark, Milwaukee, and Tampa saw violent clashes between Black residents and law enforcement, prompting a national reckoning with racial injustice. President Lyndon B. Johnson responded by forming the Kerner Commission to investigate the root causes — which concluded that America was “moving toward two societies, one Black, one white—separate and unequal.”

On May 1, 1950, Gwendolyn Brooks made history as the first African American to win the Pulitzer Prize. She received the award for her book of poetry Annie Allen, which chronicled the life of a young Black girl growing up in the inner city. Born in Topeka, Kansas, and raised on the South Side of Chicago, Brooks developed a distinctive poetic voice that blended social commentary, wit, and deep cultural insight. Her work masterfully used Black vernacular, everyday rituals, and sharp satire to confront racism, class struggle, and the complexities of Black identity. Brooks’ Pulitzer win marked a breakthrough in American literature, paving the way for generations of Black writers and poets.

On May 1, 1948, U.S. Senator Glenn H. Taylor of Idaho—then running as the Progressive Party’s vice-presidential candidate alongside Henry Wallace—was arrested in Birmingham, Alabama. His offense? Attempting to enter an interracial civil rights meeting through a door labeled “For Negroes.” Taylor refused to use the “white-only” entrance and was charged with disorderly conduct. His arrest drew national attention and underscored the deep resistance to racial integration in the Jim Crow South. Taylor’s act of solidarity with the Black community highlighted the intersection of politics and the burgeoning civil rights movement in postwar America.

On May 1, 1946, William H. Hastie was confirmed as the governor of the U.S. Virgin Islands, making history as the first African American to serve as a governor of a U.S. territory since Reconstruction. A former federal judge and distinguished legal scholar, Hastie’s appointment by President Harry S. Truman marked a major milestone in Black political leadership. His tenure symbolized a shift toward greater inclusion of African Americans in high-level government roles and set the stage for future appointments in federal and territorial governance.

On May 1, 1946, Emma Clarissa Williams, a Black educator, church leader, and activist, was named the American Mother of the Year by the American Mothers Committee of the Golden Rule Foundation. She became the first African American woman to receive the prestigious national honor, which had been previously reserved for white women. The recognition was groundbreaking at a time when segregation and systemic racism still defined much of American life.

Emma Williams was not only a devoted mother of five but also an influential leader in the Baptist church and civil society. She worked alongside her husband in ministry and served in roles that advanced community development and racial uplift. Her award signified a powerful moment of visibility and respect for Black motherhood and resilience in postwar America.

On May 1, 1941, civil rights leader A. Philip Randolph issued a bold call for 100,000 Black Americans to march on Washington, D.C., in protest of racial discrimination in the U.S. armed forces and the defense industry. With World War II escalating, Randolph recognized the hypocrisy of fighting fascism abroad while tolerating segregation and inequality at home. His mobilization campaign placed enormous pressure on President Franklin D. Roosevelt, eventually leading to Executive Order 8802, which banned discriminatory hiring in defense industries and established the Fair Employment Practices Committee (FEPC). Though the march was called off after the executive order, Randolph’s efforts laid the groundwork for the modern civil rights movement and the iconic 1963 March on Washington.

On May 1, 1930, Marion Walter Jacobs—known to the world as Little Walter—was born in Marksville, Louisiana. A revolutionary harmonica player and singer, Little Walter reshaped rhythm & blues by amplifying his harmonica, creating a raw, electric sound that would influence generations of blues and rock musicians. His hit songs like “Juke,” the first harmonica instrumental to top the R&B charts, and “My Babe,” written by Willie Dixon, became standards in the genre. As a core member of the Muddy Waters Band and a successful solo artist, Little Walter remains one of the most innovative blues musicians in history.

On May 1, 1924, Evelyn Boyd Granville was born in Washington, D.C. She would go on to become one of the first African American women to earn a Ph.D. in mathematics. Raised during segregation, Granville attended the prestigious Dunbar High School, where two dedicated teachers nurtured her interest in math. She later graduated summa cum laude from Smith College and earned her doctorate from Yale University in 1949, studying under renowned mathematician Einar Hille.

Granville’s career spanned education, government, and aerospace. She worked on critical NASA space programs, including Project Vanguard and Project Mercury, helping calculate complex rocket trajectories. Beyond her technical achievements, Granville was a fierce advocate for math education and spent decades mentoring young women and Black students in STEM.

On May 1, 1902, African American jockey Jimmy Winkfield rode Alan-a-Dale to victory, claiming his second straight win at the Kentucky Derby. Winkfield, who had also won in 1901 aboard His Eminence, became one of the few jockeys in history to win the prestigious race in back-to-back years. During the early years of the Derby, Black jockeys dominated the sport—winning 15 of the first 28 races between 1875 and 1902. Despite their early success, systemic racism and exclusion would soon push many African American riders out of the sport. Winkfield’s legacy endures as one of the greatest riders in horse racing history.

On May 1, 1867, Howard University officially opened its doors in Washington, D.C. Named after Union General Oliver O. Howard, a key figure in the Freedmen’s Bureau, the university was established to provide educational opportunities to newly emancipated African Americans in the aftermath of the Civil War. From its beginnings as a theological seminary, Howard quickly grew into a major institution of higher learning—offering liberal arts, law, medicine, and more. Today, Howard remains one of the most prestigious historically Black colleges and universities (HBCUs) in the United States, producing generations of Black leaders, scholars, and changemakers.

On May 1, 1867, the Reconstruction era entered a pivotal phase as General Philip H. Sheridan ordered the registration of voters in Louisiana, marking one of the first large-scale efforts to enroll Black men as citizens and participants in U.S. democracy. Under the Reconstruction Acts, newly freed African Americans were granted the right to vote, and military governors oversaw the process to ensure fair implementation across the former Confederate states. Voter registration in Arkansas began shortly after, and by the end of October, over 1.36 million voters—Black and white—had been registered across the South. This moment laid the foundation for the rise of Black political power during Reconstruction, including the election of Black legislators and public officials.

On May 1, 1866, one of the most violent racial attacks of the Reconstruction era erupted in Memphis, Tennessee. Over a three-day period, white mobs—including police officers and former Confederate soldiers—launched a brutal assault on Black freedmen and their white Unionist allies. The violence claimed the lives of 46 African Americans and 2 white civilians, left more than 70 people injured, and resulted in the burning of 90 Black homes, 12 schools, and 4 churches.

This atrocity was rooted in white resentment of Black freedom, labor competition, and the presence of Black Union soldiers in the city. The Memphis Massacre shocked the nation, spurred Congressional investigations, and influenced the passage of the 14th Amendment, which granted citizenship and equal protection under the law to all persons born in the United States.

On May 1, 1863, the Confederate Congress passed a chilling resolution declaring that Black Union soldiers and their white officers would not be granted the protections of lawful combatants. Instead, Black troops were to be treated as “incendiaries” and enslaved or executed upon capture. White officers leading them could be punished as criminals. This policy effectively doomed Black soldiers—many of whom were formerly enslaved—to death or re-enslavement if captured.

The resolution was a brutal response to the growing presence of African American regiments like the United States Colored Troops (USCT), whose bravery and military discipline challenged Confederate ideology and added manpower to the Union cause. The order sparked outrage in the North and led to retaliatory threats from President Lincoln, who demanded equal treatment for all Union prisoners of war.

On May 1, 1905, W.E.B. Du Bois and a group of Black intellectuals laid the groundwork for what would become the Niagara Movement—an early civil rights organization advocating for political and social rights for African Americans. Discontented with Booker T. Washington’s accommodationist approach, the group called for full civil liberties, abolition of racial discrimination, and human rights. Although it eventually disbanded, the Niagara Movement laid the ideological foundation for the NAACP, which formed a few years later. Its bold vision signaled a more direct and vocal push for equality in the early 20th century.

Russell Atkins, born May 1, 1923, in Cleveland, Ohio, became a pioneering voice in Black experimental poetry. A composer, dramatist, and founder of Free Lance, one of the earliest African American literary magazines, Atkins’ work blurred the lines between visual art, music, and poetry. Though not widely known during his early years, Atkins influenced generations of writers with his innovative “concrete” poems and politically charged themes. His work defied mainstream conventions and challenged the boundaries of form, race, and identity in American letters.

On May 1, 1992, Los Angeles erupted into widespread unrest following the acquittal of four white police officers who had brutally beaten Rodney King, a Black motorist, in a videotaped incident. The violence and destruction that followed exposed deep racial and economic inequalities within the city. The uprising lasted six days, leaving over 60 people dead and causing $1 billion in damages. Though tragic, it forced a national conversation about police brutality and systemic racism, prompting some reforms in police oversight and civil rights legislation.

On May 1, 2003, Annette Gordon-Reed received the Pulitzer Prize for her book Thomas Jefferson and Sally Hemings: An American Controversy, a work that reshaped historical discourse around race, power, and American founding myths. Though the book was published in the late ’90s, it was on May 1 that she was formally recognized for her role in proving the truth of Jefferson’s relationship with the enslaved Sally Hemings. Her scholarship challenged mainstream historians and validated oral histories long held within African American communities. Gordon-Reed’s work helped redefine American history by centering enslaved people’s voices.

In the wake of the Civil War’s end, on May 1, 1865, over 10,000 people, many of them formerly enslaved, gathered at a former Confederate prison camp in Charleston to honor Union soldiers buried in a mass grave. Led by Black community members, they exhumed the bodies for proper reburial, built a fence around the cemetery, and held a procession that included hymns, sermons, and picnics—marking one of the earliest known Memorial Day celebrations. This act of remembrance and dignity challenged the narrative of the Confederacy’s legacy and served as a symbolic claim of freedom, healing, and national unity. Though later overshadowed in popular accounts, this event remains a foundational moment in African American civic and cultural assertion during the Reconstruction era, demonstrating the role of Black Americans in shaping the nation’s commemorative traditions.

On May 1, 1950, Kwame Nkrumah led the Convention People’s Party (CPP) in launching the “Positive Action” campaign against British colonial rule in the Gold Coast. Using peaceful protests, strikes, and non-cooperation, the movement became a cornerstone of Ghana’s path to independence. Though Nkrumah was arrested shortly after, the movement gained momentum. By 1957, Ghana became the first Sub-Saharan African country to gain independence. May 1 also coincided with International Workers’ Day, amplifying the solidarity between labor rights and anti-colonial struggles. Nkrumah’s strategy inspired broader Pan-African efforts and established him as a key figure in global decolonization. The campaign fused Black self-determination with grassroots organizing, laying the groundwork for future liberation movements across Africa and the Caribbean.

May 1, 1960 marked the first celebration of International Workers’ Day in Nigeria as it approached full independence from Britain (officially granted in October that year). Nigerian trade unions and labor activists used the day to press for better wages, improved working conditions, and local control of resources. The celebration became a potent symbol of the new nation’s emerging identity, where Black workers played an active role in shaping postcolonial democracy. May Day became an annual platform for advocating labor rights and government accountability. The 1960 rally also marked a cultural shift, where Pan-African ideals and socialist labor movements influenced Nigeria’s early policy frameworks. This historic May Day helped embed organized labor into the fabric of the country’s political evolution.

While the infamous Haymarket Affair occurred in Chicago on May 1, 1886, less known is the support it garnered among Black Caribbean labor thinkers, particularly in Haiti. Haitian intellectuals and activists saw parallels between American labor repression and their own struggles under post-independence economic hardship and neocolonial pressure. Haitian newspapers reported on the protests with sympathy, interpreting the labor movement as an extension of Black resistance to economic injustice. This early expression of transnational solidarity helped frame International Workers’ Day as a global Black issue, linking race and class struggles. Haitian thinkers argued that the dignity of labor must be central to any post-slavery society and saw May 1 as a symbolic rallying cry for economic freedom across the African diaspora.

On May 1, 1994, just days after its first multiracial democratic elections, South Africa celebrated its most symbolic Workers’ Day in modern history. Nelson Mandela and the African National Congress (ANC) had just secured victory, ending decades of apartheid rule. The celebration was not only about labor rights—it was about national liberation. Black workers had long been the backbone of resistance, organizing under repressive laws and brutal conditions. May Day now symbolized a new dawn, as long-excluded communities claimed both political and economic agency. Rallies across the country were filled with hope, unity, and a call to rebuild the nation on justice and equality. It was a turning point where labor rights, civil rights, and Black empowerment visibly converged.

On May 1, 1968, just a month after Dr. King’s assassination, the Poor People’s Campaign officially launched with thousands of activists arriving in Washington, D.C. from across the country. Though multiracial, the campaign centered on Black poverty and systemic exclusion. Dr. King had envisioned a cross-class, cross-race alliance that confronted economic injustice as the next frontier of civil rights. The campaign culminated in “Resurrection City,” a tent city erected on the National Mall. May 1 symbolized the merging of labor justice with civil rights, and though met with resistance, the campaign reshaped national discussions around systemic inequality. It remains one of the boldest attempts to create a unified front against economic racism in the modern era.

Though assassinated in February 1965, Malcolm X’s final writings and speeches had a profound impact on African labor leaders who gathered on May 1 of that year across newly independent nations like Tanzania. His message of Pan-African unity, anti-imperialism, and economic self-determination was widely circulated among African trade unions. In Tanzania, President Julius Nyerere referenced Malcolm X’s calls for global solidarity against Western economic domination during a major May Day address. The convergence of Black consciousness with labor movements solidified a new era of ideological fusion across the diaspora. Malcolm’s philosophy helped labor leaders reframe their work as part of a broader decolonial and cultural struggle.

Under the socialist-leaning People’s Revolutionary Government, led by Maurice Bishop, Grenada declared May 1 a public holiday in 1978 to honor workers and their contributions to national development. Bishop’s government aligned itself with labor and peasant movements and actively promoted worker education and ownership. The decision to formalize May Day as a state holiday marked a key moment in Black Caribbean governance, where working-class power was enshrined in law and celebrated openly. Bishop’s rhetoric on this day connected local labor with global anti-capitalist struggles, particularly those in Africa and Latin America. The annual observance became a symbol of empowerment and international solidarity among Afro-Caribbean people.

In May 1935, a group of prominent African and Caribbean intellectuals, including C.L.R. James and George Padmore, met in London during May Day celebrations to discuss anti-colonial strategy and Pan-African unity. Though informal, their gathering laid the groundwork for future conferences and organizations that would drive the Pan-African movement. Discussions included worker exploitation under colonial rule, racism in Britain, and the role of diaspora writers in resistance. Their ideas would influence the 1945 Pan-African Congress in Manchester and the independence movements across Africa and the Caribbean. May 1 was chosen symbolically to connect Black liberation with the global working class.

On May 1, 1979, Brazil saw one of its largest labor protests under the military dictatorship, and Afro-Brazilian workers played a prominent role. For decades, Afro-Brazilians had been excluded from unions and public life, but this May Day, Black leaders took the stage to demand racial inclusion in labor policies. The protest also gave rise to the formation of several Afro-Brazilian labor rights organizations, including initiatives linked to cultural preservation like capoeira schools and Candomblé rights. It was a milestone for racial justice in Brazil, pushing the labor movement to confront internal racism and align more closely with Black identity politics.

While Haiti officially declared its independence from France on January 1, 1804, May 1, 1804 marks the day Jean-Jacques Dessalines publicly reaffirmed Haiti’s Black sovereignty and formally named it the “Empire of Haiti”, addressing global audiences. On this date, Haiti issued declarations to the world affirming that it would be a nation led by formerly enslaved people, free of colonial or racial domination. Dessalines’ government enshrined this vision in public ceremonies and diplomatic overtures to foreign powers—while making clear that Haiti would not tolerate the return of slavery or European control.

This was not just about independence—it was a bold ideological rejection of white supremacy and plantation capitalism. Haiti became the first nation in the world to permanently abolish slavery and assert Black governance at the national level. It inspired fear in colonial empires, solidarity among Black thinkers globally, and remains one of the most revolutionary declarations of Black autonomy in modern history.

On May 2, 1920, the first official game of the Negro National League (NNL) was played, marking a historic moment in African American sports history. The game took place in Indianapolis between the Indianapolis ABCs and the Chicago American Giants. Founded earlier that year by baseball legend Rube Foster, the NNL became the first successful, organized Black baseball league in the United States, providing a professional platform for African American players who were barred from Major League Baseball due to segregation.

On May 2, 2002, during a televised panel and later documented in academic publications, historians emphasized a striking truth: the American Revolution was partially financed through profits from slavery. While white Americans fought for liberty from British rule, many were simultaneously benefiting from the labor of enslaved Africans. Cotton, tobacco, sugar, and indigo — products grown by enslaved people — were traded for weapons, supplies, and funding, especially with France during the War of Independence. One historian notably remarked, “Americans purchased their freedom with products grown by slaves.”

This interpretation sparked debate but highlights a sobering reality: the quest for liberty in the U.S. was deeply entangled with the economic foundation of slavery — a paradox at the heart of the nation’s founding.

On May 2, 1992, the city of Los Angeles began the massive cleanup and rebuilding process following five days of unrest sparked by the acquittal of four LAPD officers in the brutal beating of Rodney King. The uprising, often mislabeled as “riots,” reflected decades of racial injustice, police brutality, and economic inequality. The unrest resulted in 58 deaths, over 2,300 injuries, 600 reported fires, and more than $1 billion in property damage. In the aftermath, community leaders, residents, and city officials mobilized to repair not only buildings, but also the social fabric of neighborhoods like South Central L.A. The event marked a national reckoning with systemic racism and would later inspire reforms and dialogue around policing and equity in America.

On May 2, 1968, Reverend Ralph Abernathy officially launched the Poor People’s Campaign with a march on Washington, D.C., just one month after the assassination of his close friend and fellow civil rights leader Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. The campaign was King’s final vision—a multiracial movement aimed at fighting poverty through economic justice and policy change. Abernathy, now leading the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), brought thousands of marchers to the nation’s capital to demand jobs, housing, and a guaranteed income. The campaign would culminate in Resurrection City, a tent encampment on the National Mall, symbolizing the plight of America’s poor.

On May 2, 1963, more than 2,500 African American children, teenagers, and a few white allies were arrested in Birmingham, Alabama, during a mass protest against racial segregation. Known as the start of the Children’s Crusade, this pivotal moment in the Civil Rights Movement saw young people leave school to march peacefully for justice. Despite their nonviolent stance, many were met with fire hoses, police dogs, and mass incarceration under the orders of Public Safety Commissioner Bull Connor. The shocking images of children being brutalized gained national attention and pressured federal authorities to take action, ultimately helping to pave the way for the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

On May 2, 1870, William J. Seymour was born in Centerville, Louisiana. The son of formerly enslaved parents, Seymour would rise to become one of the most influential religious leaders in American history. As the central figure of the 1906 Azusa Street Revival in Los Angeles, Seymour is widely credited as the driving force behind the rise of Pentecostalism in the United States—a movement characterized by expressive worship, speaking in tongues, and a strong emphasis on the Holy Spirit.

What made Seymour’s leadership revolutionary was not just his theology, but his commitment to racial unity in worship. At a time when Jim Crow laws enforced segregation, the Azusa Street Revival welcomed people of all races to worship together, breaking social norms and igniting a global spiritual movement. Today, Pentecostalism has over 500 million adherents worldwide, with Seymour’s influence still at its core.

On May 2, 1845, Macon Bolling Allen became the first African American licensed to practice law in Massachusetts. A year earlier, in 1844, Allen had already made history by becoming the first Black person admitted to the bar in the United States, in the state of Maine. Overcoming deep racial prejudice and limited access to formal legal education, Allen taught himself law and passed rigorous examinations in both states. He would later go on to become one of the first Black judges in the U.S. as well. His achievements laid the groundwork for future generations of African American legal professionals.

On May 2, 1844, Elijah McCoy was born in Colchester, Ontario, to formerly enslaved parents who escaped through the Underground Railroad. A brilliant mechanical engineer and inventor, McCoy would go on to secure over 50 patents, most notably for an automatic lubricating cup that revolutionized steam engine maintenance in trains and factory machines. His inventions were so effective and trusted that clients would insist on getting “the real McCoy,” a phrase that became synonymous with authenticity and quality. McCoy’s legacy as a master Black inventor defied the racial barriers of his time and left a lasting impact on industrial innovation worldwide.

On May 2, 1803, Denmark Vesey, a formerly enslaved man, purchased his freedom with $600 he had won through a local lottery. While this event occurred in the U.S., its significance extends across the African diaspora due to Vesey’s later role in organizing one of the most ambitious planned slave revolts in the Atlantic world. Drawing inspiration from the Haitian Revolution, Vesey sought to unite thousands of enslaved and free Black people in Charleston to rise up and escape to Haiti—a Black republic that symbolized liberation for the African diaspora. Though the revolt was ultimately suppressed in 1822, Vesey’s vision embodied transnational Black resistance and Pan-African unity. His actions inspired abolitionists, revolutionaries, and writers across the Americas and Caribbean. May 2 marks not only his personal emancipation, but the beginning of a legacy that challenged white supremacy across borders and centuries.

On May 2, 1803, Toussaint Louverture, the brilliant leader of the Haitian Revolution, died in a French prison in Fort-de-Joux. Louverture had been betrayed by Napoleon’s forces after being lured into negotiations and deported to France. As the architect of the Haitian independence movement, Louverture transformed a slave uprising into the first successful revolution led by formerly enslaved people, paving the way for Haiti to become the first Black republic in 1804. Though he died before the final victory, his vision and strategy laid the foundation for independence. His death marked a turning point in colonial resistance movements and remains a symbol of liberation and betrayal. Toussaint’s legacy endures across the African diaspora as a representation of resilience, intellect, and uncompromising resistance to slavery.

On May 2, 1994, just days before officially becoming South Africa’s first Black president, Nelson Mandela cast his ballot in the country’s first multiracial democratic elections. For a man who had spent 27 years in prison fighting apartheid, this act held profound symbolic power. Mandela’s vote represented the dismantling of a century of white minority rule and the birth of a new democratic era in South Africa. The election, which began on April 27 and concluded in early May, was marked by unprecedented national unity and optimism. Mandela’s action was celebrated globally as a triumph of perseverance, reconciliation, and peaceful transition. It resonated across post-colonial nations and civil rights movements worldwide, serving as an inspiration for democratic governance and racial justice.

On May 2, 1984, Michael Jackson embarked on a major tour in Japan, marking one of the earliest large-scale performances by a Black American entertainer in Asia. Jackson’s influence had already begun reshaping global pop culture, and his appearance captivated Japanese audiences and media. He broke through racial and cultural boundaries, opening doors for other Black artists in regions previously dominated by Western or local performers. Jackson’s visit was not just about music—it was about cultural diplomacy. He became a symbol of unity, bringing together diverse audiences and introducing them to Black American art, style, and humanitarianism. His tour would later inspire similar visits by global Black icons, contributing to the internationalization of hip hop, R&B, and Black cultural expression.

On May 2, 1863, Black Union soldiers fighting under General David Hunter faced deadly resistance in the South during early Civil War skirmishes. Hunter was one of the first Union generals to arm formerly enslaved men, defying orders and precedent. Though these early actions were met with controversy and the threat of Confederate reprisals, they marked a critical turning point in recognizing Black military service as legitimate and essential. The bravery shown by these early volunteers laid the groundwork for the eventual creation of the United States Colored Troops (USCT). Their sacrifice on this day was among the earliest in a broader campaign that saw nearly 200,000 Black soldiers fight for the Union. It also had global implications, showcasing the courage of Black men in battle and reinforcing abolitionist momentum worldwide.

On May 2, 1973, President Mobutu Sese Seko of Zaire (now the Democratic Republic of Congo) formally advanced his policy of “Authenticité,” a program aimed at rejecting colonial culture and restoring African identity. The policy encouraged citizens to abandon European names, dress in traditional attire, and adopt indigenous languages and customs. While the intent was to foster pride and unity in postcolonial Zaire, it also reinforced Mobutu’s authoritarian regime. Internationally, “Authenticité” was a key example of how African nations grappled with postcolonial identity and sovereignty. Although controversial, the movement inspired other African leaders to explore cultural revitalization as a form of resistance to neocolonial influence and to assert a distinctly African modernity.

On May 2, 2005, Ellen Johnson Sirleaf officially launched her campaign for the presidency of Liberia. A Harvard-educated economist and long-time advocate for development and women’s rights, Sirleaf’s candidacy was a groundbreaking moment in African politics. At a time when Liberia was still recovering from civil war, her campaign brought hope, stability, and international respect. She won the election later that year, becoming the first elected female head of state in Africa. Her leadership ushered in an era of reconstruction and reform, and she became a symbol of female empowerment across the continent. Her campaign’s launch marked a historic milestone, challenging gender norms and laying a path for future women leaders globally.

On May 2, 1969, civil rights activist James Forman interrupted a service at Riverside Church in Detroit to deliver the “Black Manifesto,” demanding $500 million in reparations from white churches and synagogues for their complicity in slavery and segregation. Forman, a former leader in the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), framed the demand as a moral obligation rooted in historical justice. The manifesto sparked national debate and led to the formation of reparations task forces across the U.S. and abroad. Though controversial, the action brought renewed global attention to the issue of reparations, influencing policy discussions in Caribbean nations and later efforts by African Union member states. May 2 became a critical day in the history of economic justice advocacy for the African diaspora.

On May 2, 2000, the BBC launched “Black Britain,” a landmark program focused on the lives, struggles, and triumphs of Black communities in the UK. The show was part of a broader initiative to improve representation of ethnic minorities on British television. “Black Britain” tackled issues from policing to cultural celebration, giving a platform to stories often marginalized in mainstream media. The program played a key role in shaping the public discourse on race, identity, and inclusion in Britain. It also inspired similar media initiatives across Europe and former British colonies. Its debut marked an important moment in the cultural affirmation of Black British identity and media empowerment.

On May 2, 1948, future Ghanaian president Kwame Nkrumah launched the Accra Evening News, a revolutionary newspaper that became the mouthpiece of the independence movement in the Gold Coast. At a time when colonial media dominated the public narrative, Nkrumah’s paper gave voice to nationalist sentiment, exposed British injustices, and organized resistance. It was bold, defiant, and widely read among young activists. The Accra Evening News would become a cornerstone of political education and grassroots mobilization, influencing anti-colonial movements across Africa. Its founding on this day signaled a new era in African journalism—one that sought not just to report facts but to liberate minds.

On May 2, 1872, the Freedmen’s Bureau oversaw the completion of a school for African Americans in Galveston, Texas, furthering its mission to support newly freed Black citizens after the Civil War. Though short-lived, the Bureau played a critical role in building schools, hospitals, and housing for formerly enslaved people. The Galveston school provided formal education to children and adults who had previously been denied access to literacy. Teachers, often from the North, risked violence from hostile locals, yet persisted in their mission. This school became a symbol of Reconstruction-era hope and the broader Black commitment to education as a pathway to freedom and citizenship. The legacy of these schools lives on through the historically Black colleges and universities (HBCUs) that emerged during this period.

On May 2, 1983, Alice Walker was awarded the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction for her novel The Color Purple, making her the first African American woman to receive the honor. Her groundbreaking work, published in 1982, tells the story of Celie, a Black Southern woman who endures abuse and hardship but ultimately finds self-empowerment and spiritual liberation. Walker’s prose vividly captures the intersectionality of race, gender, and class in early 20th-century America. The novel was praised for its emotional depth and cultural authenticity, though it also faced criticism for its depiction of Black male characters. The Color Purple has since become a cultural cornerstone, adapted into a critically acclaimed film and Broadway musical. Walker’s Pulitzer win marked a watershed moment for Black women writers and opened doors for a new generation of voices in literature.

On May 2, 1943, the Tuskegee Airmen—America’s first Black military aviators—began deploying for overseas combat operations during World War II. Trained at the Tuskegee Institute in Alabama under the Army Air Corps, these men faced racial discrimination both in the military and in society. Despite doubts about their capabilities, they proved to be some of the most skilled and disciplined pilots of the war. Flying primarily in Europe, they escorted bombers and achieved one of the lowest loss records in the war. Their performance helped challenge prevailing racist assumptions and laid the groundwork for President Truman’s 1948 executive order to desegregate the armed forces. The deployment on May 2 marked a turning point in U.S. military history and stands as a symbol of perseverance and patriotism.

On May 2, 1974, after a high-profile trial, Black activist and scholar Angela Davis was acquitted of all charges related to a 1970 courtroom kidnapping and murder. Davis, a prominent figure in the Black Power and Communist movements, had been accused of supplying weapons used in the incident. Her arrest and trial sparked global protests and brought attention to racial bias in the U.S. legal system. Her defense highlighted systemic injustice, and the jury ultimately found insufficient evidence to convict her. Davis’s acquittal was seen as a major victory for civil liberties and political activism. She went on to become a renowned educator and author, continuing her advocacy for prison abolition and racial justice.

On May 2, 1865, just weeks after the Civil War ended, Congressman Thaddeus Stevens delivered a fiery speech demanding full citizenship and suffrage for freed African Americans. As a leader of the Radical Republicans, Stevens pushed for Reconstruction policies that would dismantle the remnants of slavery and ensure civil rights. His speech laid the groundwork for future amendments—the 14th and 15th—that would enshrine Black citizenship and voting rights into the Constitution. Although fiercely opposed by Southern lawmakers, Stevens’ advocacy helped shift the national conversation toward racial equality, even as his vision was only partially realized during his lifetime. His call on May 2 helped ignite the legal and political battles that would define Reconstruction and beyond.

On May 2, 1930, theologian and mystic Howard Thurman was appointed Dean of Rankin Chapel at Howard University. As one of the most influential Black religious thinkers of the 20th century, Thurman bridged the worlds of theology, mysticism, and social justice. He mentored future leaders like Martin Luther King Jr. and emphasized the power of nonviolence, inner strength, and spiritual liberation. His tenure at Howard expanded the university’s religious life and gave students a model of ethical leadership rooted in the Black prophetic tradition. Thurman’s interfaith and intercultural work would later inspire global movements for peace and reconciliation.

On May 2, 1895, Booker T. Washington hosted a major conference at Tuskegee Institute, bringing together Black educators, farmers, and business leaders to promote industrial and vocational training. The Tuskegee Negro Conference, as it was called, sought to provide practical strategies for economic advancement in the face of Jim Crow laws and disenfranchisement. Washington emphasized self-help, land ownership, and trades as tools for racial uplift. Although his philosophy of accommodationism was later challenged by W.E.B. Du Bois and others, Washington’s work laid an essential foundation for Black educational infrastructure in the South. The annual conference became a key forum for community coordination and strategic planning.

Macon Bolling Allen, first African American lawyer admitted to the bar, passed examination at Worchester, Massachusetts. Macon B. Allen was the first African American lawyer to be admitted to a state bar, and the first African American to hold a judicial position in the United States. Macon was born in Indiana in 1816 and learned to read and write on his own. He worked as a teacher, but moved to Maine in his late twenties, serving there as an apprentice in a law firm.

After passing the Maine Bar Exam in 1844, Allen could not find work because of his race. He moved to Boston, where he opened the first black law office in the United States. In 1848, Allen became Justice of the Peace for Middlesex County in Massachusetts. He later moved to South Carolina, where he was appointed as a judge in the Inferior Court of Charleston in 1873. He also served as Probate Judge of Charleston in 1874. Allen practiced law until his death in 1894.

On May 2, 1967, more than 100 Black students at Northwestern University in Evanston, Illinois, seized the Bursar’s (Finance) Office in a bold demonstration against racial discrimination and academic exclusion. The protest lasted 38 hours and became a pivotal moment in campus activism. The students presented a list of demands calling for a Black studies curriculum, increased Black student enrollment, better support for Black students, and the establishment of a Black student union. Their efforts led to meaningful changes, including the creation of the Department of African American Studies and more inclusive university policies. The Bursar’s Office Takeover remains a landmark example of student-led reform in higher education.

On May 2, 1948, the United States Supreme Court issued a landmark civil rights ruling in Shelley v. Kraemer, declaring that courts could not enforce racially restrictive covenants in property deeds. These covenants, which were widespread across the country, barred Black families and other minorities from buying or occupying homes in certain neighborhoods. The decision did not outlaw the covenants themselves but prohibited state and federal courts from upholding them—effectively stripping them of legal power. The case was brought by the Shelley family, African American homeowners in St. Louis, Missouri, who challenged the systemic housing discrimination that had long excluded Black Americans from suburban homeownership and generational wealth. This ruling paved the way for broader challenges to housing segregation and remains a foundational case in the history of U.S. civil rights law.

From May 1 to May 3, 1866, one of the earliest post–Civil War race massacres occurred in Memphis, Tennessee. White mobs—including police officers and former Confederate soldiers—attacked Black communities in response to tensions over Black Union soldiers returning home and the growing push for civil rights. Over the three-day rampage, at least 46 African Americans were killed, more than 70 were injured, and over 90 Black homes, 12 schools, and 4 churches were burned to the ground. The massacre shocked the nation and fueled support for Radical Reconstruction policies and the 14th Amendment. It remains a sobering example of the violent backlash to Black freedom in the Reconstruction era.

James Brown, one of the most influential figures in American music, was born on May 3, 1933, in Barnwell, South Carolina. Brown helped pioneer soul, funk, and rhythm and blues, leaving an indelible mark on 20th-century popular music. His energetic performances, revolutionary rhythms, and vocal intensity paved the way for countless artists across genres. Beyond music, Brown became an advocate for Black empowerment during the Civil Rights Movement, famously promoting self-reliance with anthems like “Say It Loud – I’m Black and I’m Proud.” His influence stretched from Motown to hip-hop, earning him numerous accolades including inductions into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame and a Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award.

On May 3, 1960, the U.S. Congress passed the Civil Rights Act of 1960, aiming to address racial discrimination in voting. Building on the earlier 1957 Act, this legislation introduced federal inspection of local voter registration polls and penalties for obstructing Black Americans from voting. While limited in scope, it signaled growing federal willingness to intervene in Southern states that systematically disenfranchised African Americans. The 1960 Act laid groundwork for the more powerful Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965, pivotal in dismantling Jim Crow laws. It demonstrated that legal pressure and organized activism were beginning to crack the foundations of segregation.

On May 3, 1978, the National Urban League, under Vernon Jordan’s leadership, organized a major March on Washington to demand economic opportunities and justice for African Americans. Unlike the 1963 march, this protest was Black-led at every level, reflecting the post-Civil Rights era’s emphasis on Black agency. Demonstrators called for fair employment, better housing, and investment in urban communities. Though it garnered less media coverage than earlier marches, it was significant for pushing the dialogue beyond civil rights toward economic equity—a struggle that remains ongoing today.

On May 3, 1963, during the Birmingham Campaign in Alabama, hundreds of young Black protesters faced fire hoses and police dogs under Bull Connor’s orders. Captured on national television, these brutal scenes shocked the nation and the world, galvanizing support for civil rights legislation. The campaign, led by Martin Luther King Jr. and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), aimed to dismantle Jim Crow segregation in the city known as “the most segregated in America.” May 3rd marked a turning point, with children leading “Children’s Crusade” marches, demonstrating remarkable courage and shifting public opinion irreversibly.

John Brown, a white abolitionist who would become a fierce ally to Black freedom fighters, was born on May 3, 1808, in Connecticut. Though controversial, Brown’s deep conviction that slavery must be eradicated by any means—even violence—made him a singular figure in American history. His 1859 raid on Harper’s Ferry aimed to ignite a slave rebellion. Though the raid failed and Brown was executed, his actions helped heighten tensions leading to the Civil War. Many Black leaders, including Frederick Douglass and later W.E.B. Du Bois, recognized Brown as a martyr for the cause of Black liberation.

On May 3, 1980, musician and cultural advocate Kenny Gamble met with political leaders to push for the official recognition of June as Black Music Month. Although President Jimmy Carter formally proclaimed it later that year, the groundwork began with this pivotal May meeting. Black Music Month honors the immeasurable contributions of African Americans to music genres including jazz, gospel, blues, R&B, hip-hop, and rock and roll. It institutionalized a national celebration of Black creativity and cultural impact, highlighting a central pillar of American—and global—artistic life.

Elmer A. Carter, a groundbreaking social worker and civil rights leader, passed away on May 3, 1949. He was the first African American to head a New York State agency, serving on the State Commission Against Discrimination. Carter championed fair employment practices and was instrumental in drafting early civil rights laws. His career exemplified the growing political influence of African Americans in the early 20th century, setting a foundation for future generations of Black public officials.

Although the official opening was May 23, the previews for Shuffle Along—the groundbreaking all-Black Broadway musical—began on May 3, 1921. Written by Noble Sissle and Eubie Blake, it broke racial barriers, proving that Black performers could command Broadway audiences. Its success helped usher in the Harlem Renaissance by launching careers of major stars like Josephine Baker and Paul Robeson. Shuffle Along challenged stereotypes and expanded opportunities for African American artists in mainstream theater, influencing American culture for decades.

Septima Clark was born on May 3, 1898, in Charleston, South Carolina. A pioneering educator and activist, she understood that literacy and education were essential tools for Black empowerment. Clark developed citizenship schools that taught Black adults how to read, write, and pass voter literacy tests. Her work greatly expanded the base of civil rights activism and voter participation, particularly in the South. Often overshadowed by more famous figures, Clark’s grassroots leadership made the broader movement possible, earning her the title “Mother of the Civil Rights Movement.”

Elijah McCoy, born in Colchester, Ontario, to formerly enslaved parents, became one of the most prolific inventors in North America. His groundbreaking work in lubrication systems for steam engines revolutionized industry and transportation. McCoy’s automatic lubricators allowed trains and machinery to run longer and more efficiently, earning him 57 patents. His inventions were so respected that buyers would ask for “the real McCoy,” coining the famous phrase. Despite his genius, McCoy faced racial barriers that limited his business opportunities. Nevertheless, he persisted, becoming a symbol of Black ingenuity and perseverance in the face of systemic discrimination. His life inspired generations of Black inventors.

After decades of anti-colonial struggle against Portuguese rule and a long civil war, Angola was officially admitted as a full member of the United Nations on May 3, 1991. Angola’s independence in 1975 marked a major moment in African decolonization. However, civil conflict, often fueled by Cold War politics, ravaged the nation. By joining the UN, Angola took a significant step toward international recognition, diplomacy, and rebuilding efforts. This event symbolized the ongoing journey of African nations asserting their sovereignty on the world stage, striving for peace, self-determination, and global partnership.

Although Jomo Kenyatta died in August, May 3, 1978, marked an important national day of mourning declared in his honor by many African states. Kenyatta, often called the “Father of the Nation,” led Kenya to independence from British colonial rule in 1963. His Pan-African ideals and emphasis on African sovereignty inspired liberation movements across the continent. While his presidency was not without controversy, Kenyatta remains a towering figure in African history for his leadership, advocacy for land rights, and promotion of national unity amidst ethnic diversity.

On May 3, 1948, Jamaica officially celebrated its first national Labor Day to honor the critical role of workers, particularly Black laborers who fought for social and economic reforms. Labor Day in Jamaica originated in recognition of the 1938 labor uprisings that had sparked greater rights for working-class Jamaicans. These uprisings were pivotal to Jamaica’s path toward independence in 1962. The observance of Labor Day celebrated solidarity, worker dignity, and Black leadership in shaping a fairer society, setting a precedent for similar recognitions across the Caribbean.

On May 3, 1791, Toussaint Louverture achieved his first significant military victory against French forces in what would become the Haitian Revolution. The success marked a powerful signal that enslaved Africans in Saint-Domingue (now Haiti) could organize and defeat colonial armies. Louverture’s leadership not only advanced the Haitian cause but would eventually lead to Haiti becoming the first Black republic and the first nation to abolish slavery entirely. His early victories became inspiration for freedom movements worldwide, showing that Black liberation was possible through courage and strategic brilliance.

Zakaria Mohieddin, a key figure in Egypt’s 1952 revolution that ended monarchy rule, died on May 3, 1969. Though not as globally recognized as Gamal Abdel Nasser, Mohieddin was a crucial architect in modernizing Egypt and asserting African and Arab independence from colonial influence. His leadership during tumultuous times underscored the broader Pan-African and Pan-Arab efforts to resist imperialism. His policies influenced many African nations struggling for sovereignty in the mid-20th century, leaving an enduring if understated legacy in Black internationalist history.

On May 3, 1960, the foundations of what would become the Nigeria Labour Congress were laid, unifying various labor movements under a common banner. The NLC would grow to become the largest labor organization in Africa, advocating for workers’ rights, economic justice, and democracy. The creation of the NLC reflected the broader push for national dignity and independence from colonial and neocolonial economic systems, serving as a model for worker solidarity movements across the African continent.

Though the kidnapping of 276 schoolgirls by Boko Haram in Chibok, Nigeria, occurred on April 14, the #BringBackOurGirls movement reached peak global attention by May 3, 2014. Black activists, celebrities, and political figures worldwide rallied to demand action. The campaign highlighted the intersecting struggles of racial injustice, gender oppression, and neocolonial violence faced by African communities. While many girls were later rescued or escaped, the tragedy underscored the urgent need for international solidarity in protecting vulnerable Black lives from extremist violence and systemic neglect.

On May 3, 1965, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. delivered a powerful speech in London condemning apartheid in South Africa and linking it to racial injustice worldwide. Speaking at the London Hilton to an international audience, King declared that the fight for civil rights in the U.S. was inseparable from the global fight against colonialism and racial oppression. His advocacy reinforced the growing international movement against apartheid and emphasized solidarity across borders. The speech helped mobilize greater British and European support for sanctions against South Africa.

On May 3, 1948, Kwame Nkrumah, galvanized by the recent Accra Riots and the failure of colonial reforms, began organizing the political movement that would evolve into the Convention People’s Party (CPP). While officially founded in 1949, May 3 marks the moment Nkrumah’s vision crystallized — shifting from advocacy to mass mobilization for African self-governance. He broke from moderate nationalist groups, emphasizing “self-government now” rather than gradual independence. His work laid the groundwork for Ghana’s eventual freedom in 1957, making it the first sub-Saharan African nation to break colonial rule. This early organizing reflected a radical Pan-African strategy that would ripple across the continent. Nkrumah’s May 3rd efforts weren’t just national; they symbolized the rising call for Black sovereignty, dignity, and unity at a global scale, inspiring decolonization movements from Africa to the Caribbean.

On May 4, 1897, inventor J.H. Smith, an African American innovator, was awarded U.S. Patent No. 581,785 for a rotary lawn sprinkler. Smith’s invention improved the even distribution of water across lawns and gardens, using a rotating nozzle to deliver consistent pressure. His design helped shape the modern irrigation systems used in residential and agricultural landscaping today. Smith’s achievement reflects the often-overlooked contributions of Black inventors to everyday conveniences and technological advancement during the late 19th century.

On May 3, 1896, African American cowboy Bill Pickett became widely recognized as the inventor of bulldogging—a daring rodeo technique where a rider leaps from a horse to wrestle a steer to the ground. Inspired by how trained bulldogs helped catch stray cattle, Pickett adapted the method using his own skill and grit. His version included a now-retired tactic of biting the steer’s upper lip while pulling it off balance—a dramatic move that amazed crowds across the Wild West and helped shape modern steer wrestling in rodeos. Pickett toured with the Miller Brothers’ 101 Ranch Wild West Show and became one of the first Black cowboys to gain national fame. His legacy lives on as a trailblazer in both rodeo sports and African American frontier history.

On May 4, 1961, thirteen courageous civil rights activists—seven Black and six white—departed Washington, D.C., on Greyhound and Trailways buses to challenge segregated bus terminals across the American South. Known as the Freedom Riders, they tested the Supreme Court’s decision in Boynton v. Virginia (1960), which outlawed segregation in interstate bus and rail travel.

Organized by the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), the riders faced threats, mob violence, and arrests as they journeyed through Virginia, the Carolinas, Georgia, Alabama, and Mississippi. Their bravery sparked a national movement and drew international attention to the injustices of Jim Crow segregation, ultimately pressuring the federal government to enforce desegregation laws more strictly.

On May 4, 1891, Dr. Daniel Hale Williams founded Provident Hospital and Training School in Chicago, Illinois—the first interracial hospital in the United States. At a time when African Americans were often denied treatment at white hospitals, Dr. Williams created a facility where Black patients could receive quality care and where Black medical professionals could train and work. Provident not only offered lifesaving services, but it also became a pioneering institution for nursing and surgical education. Just two years later, Dr. Williams would perform one of the first successful open-heart surgeries at this very hospital, cementing both his and the institution’s place in medical history.

On May 4, 1864, General Ulysses S. Grant launched the Overland Campaign by crossing the Rapidan River, initiating a fierce and prolonged duel with Confederate General Robert E. Lee. While Grant’s main forces engaged Lee in the bloody Wilderness battles, a lesser-known but critical front was unfolding under Major General Benjamin Butler. Commanding the Army of the James, Butler included nearly 1,800 Black cavalrymen and multiple regiments of Black infantry. Though often sidelined in historical accounts, these soldiers—many formerly enslaved—played a pivotal role in seizing key Confederate positions and disrupting supply lines. Butler, a vocal advocate for Black troops, gave them front-line responsibilities and publicly praised their valor, further validating their place in the Union war effort.

Frederick Douglass, renowned abolitionist and statesman, delivered a powerful address during national labor rallies linked to the Haymarket Affair. Although primarily remembered for his anti-slavery work, Douglass championed workers’ rights late in life, recognizing that economic injustice and racial injustice were intertwined. His speech emphasized solidarity across racial and labor lines, urging Americans to honor the dignity of all laborers, black and white alike. Douglass’s commitment to both racial and economic equality demonstrated his broader vision for America — one that encompassed not only freedom from slavery but also freedom from economic oppression.

On May 4, 1910, Booker T. Washington officially launched National Negro Health Week. Alarmed by the devastating impact of preventable diseases within Black communities, Washington called for coordinated health campaigns focused on hygiene, sanitation, and medical access. The initiative empowered African Americans to take proactive steps toward improving community health. Supported by Black churches, schools, and the U.S. Public Health Service, the campaign eventually expanded into broader public health efforts that laid foundations for future health equity movements. Washington’s vision connected physical health with economic and social progress.

Born May 4, 1928, in Liberia, Hosanna Kabakoro later became a U.S.-based journalist who used her platform to advocate for African rights during the Civil Rights era. Kabakoro’s writing highlighted the interconnectedness of African independence movements and African American struggles for equality. Her work bridged diasporic conversations, encouraging solidarity and shared political strategies. Although less widely known today, Kabakoro’s contributions helped lay groundwork for Pan-African thought in American media.

The Free South Theatre was founded on May 4, 1946, in Atlanta, Georgia, as one of the first Black-owned and operated theater companies focused on telling authentic African American stories. At a time when mainstream American theaters largely excluded Black artists or presented stereotyped depictions, the Free South Theatre became a space for genuine artistic expression and political resistance. It paved the way for later groups like the Negro Ensemble Company, advancing Black narratives on stage and providing critical training grounds for young Black actors, writers, and directors.

On May 4, 1942, Doris “Dorie” Miller, an African American sailor, was awarded the Navy Cross for his heroic actions during the attack on Pearl Harbor. As a cook aboard the USS West Virginia, Miller manned anti-aircraft guns during the attack—despite having no formal training—and helped carry wounded sailors to safety. His bravery under fire challenged racial stereotypes within the military and symbolized Black Americans’ commitment to the defense of a country that often marginalized them. Miller’s recognition was a powerful, though rare, acknowledgment of African American valor in World War II.

On May 4, 1956, as the Montgomery Bus Boycott passed the five-month mark, national media coverage of the movement exploded. Photos and reports of African Americans walking miles to work or organizing carpools began appearing in newspapers across the country. The boycott, sparked by Rosa Parks’ arrest in December 1955, was a major early victory for the Civil Rights Movement. The persistence of Montgomery’s Black citizens showcased the power of economic activism and mass mobilization, helping catapult a young Martin Luther King Jr. into national prominence.

On May 4, 1969, tensions were high at historically Black Jackson State University in Mississippi, part of the nationwide wave of student activism against racism and the Vietnam War. Protests erupted following years of police brutality. State police opened fire into a women’s dormitory, killing two students and injuring several others. Although less widely remembered than the Kent State shootings days later, the Jackson State killings underscored how Black students faced deadly repression — often with little national outrage. It became a rallying cry for greater protection of Black civil rights.

On May 4, 1988, Bill and Camille Cosby announced a historic $20 million donation to Spelman College, the prestigious historically Black women’s college in Atlanta. At the time, it was the largest single donation ever made to a historically Black college or university (HBCU). The gift funded a major endowment, scholarships, and campus development projects, setting a new benchmark for philanthropic investment in Black higher education. While Cosby’s legacy has become controversial in later years, the donation played a key role in strengthening Spelman’s academic and financial standing.

On May 4, 1992, Carol Moseley Braun won the Democratic primary for U.S. Senate in Illinois, putting her on the path to become the first African American woman elected to the Senate later that year. Her victory represented a major breakthrough in American politics, shattering racial and gender barriers in one of the nation’s most powerful institutions. Moseley Braun’s campaign emphasized civil rights, women’s rights, and a progressive economic agenda, resonating with diverse coalitions of voters eager for change in the aftermath of the Los Angeles riots.

On May 4, 1865, the 1st South Carolina Volunteers, one of the first official African American regiments in the Union Army, was honorably disbanded after the end of the U.S. Civil War. Composed largely of formerly enslaved men, the regiment proved African Americans could fight courageously and effectively. Their service challenged racist assumptions of the era and paved the way for broader Black participation in the U.S. military. Many veterans went on to advocate for Reconstruction-era reforms and civil rights, demonstrating that their fight for freedom extended far beyond the battlefield.

Hubert Harrison, born May 4, 1891, in St. Croix, became one of the most influential Black activists and thinkers in early 20th-century America. Often called “The Father of Harlem Radicalism,” Harrison was a brilliant orator, writer, and critic who inspired movements for racial equality, labor rights, and socialism. He founded the Liberty League and the Voice newspaper, promoting Black self-determination and political consciousness. His ideas helped set the stage for the Harlem Renaissance and the later civil rights movement. Harrison’s transnational Caribbean perspective also connected struggles for Black liberation across the globe.

Kwame Nkrumah, born May 4, 1904, in Nkroful, Gold Coast (now Ghana), became the first Prime Minister and President of independent Ghana. A visionary Pan-Africanist, Nkrumah led the Gold Coast’s struggle against British colonial rule, inspiring African liberation movements continent-wide. He emphasized education, industrialization, and unity among African nations. Though later overthrown, his leadership and ideas profoundly influenced the decolonization of Africa and the broader Black liberation struggle worldwide. Nkrumah’s life symbolizes the global reach of Black independence and self-governance movements in the 20th century.

On May 4, 1919, Marcus Garvey’s Negro World newspaper officially launched its expanded international operations. Published by the Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA), the paper circulated across Africa, the Caribbean, and the Americas, promoting Black pride, economic independence, and Pan-Africanism. Written in English, Spanish, and French, Negro World became a crucial vehicle for Garvey’s “Back to Africa” movement and a powerful counterforce against colonial narratives. Despite being banned in many colonies, it found secret readerships, fueling global Black solidarity and resistance against imperialism.

Born on May 4, 1948, in Monrovia, Liberia, George Weah rose from humble beginnings to become one of Africa’s greatest footballers and later the President of Liberia. Known for his dynamic playing style, Weah won FIFA’s World Player of the Year and the Ballon d’Or, the first and only African to do so. After retiring from sports, he turned to politics, winning Liberia’s presidency in 2017. His life story exemplifies resilience, ambition, and service, inspiring millions across Africa and the Black diaspora to believe in transformational leadership through perseverance.

On May 4, 1956, while visiting the Gold Coast (soon-to-be Ghana), Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. delivered a private speech to a group of Ghanaian parliamentarians about the global fight for freedom and justice. Dr. King’s visit symbolized the deep ties between the African American civil rights movement and African liberation struggles. He later described Ghana’s independence as a “new African dawn” and used the experience to inspire his later activism in the United States. This day highlighted the interconnectedness of freedom movements among people of African descent worldwide.

On May 4, 1969, Fred Hampton, charismatic leader of the Illinois chapter of the Black Panther Party, delivered a stirring speech at the University of Illinois at Chicago Circle. He emphasized the need for multi-racial class solidarity, radical social programs, and revolutionary consciousness. Hampton’s organizing skill drew attention from both supporters and the FBI, leading to his assassination later that year. His speech exemplified the powerful role of young Black leaders in mobilizing resistance and inspired movements from the U.S. to Africa to rethink how liberation could be achieved.

On May 4, 1978, Senegalese scholar and activist Alioune Diop died. Diop founded Présence Africaine, a Paris-based journal and publishing house that became a cornerstone of Black intellectual and literary life in the 20th century. Through his work, Diop nurtured and connected African, Caribbean, and African American writers such as Aimé Césaire, Léopold Senghor, and Frantz Fanon. Présence Africaine helped catalyze Negritude, Pan-Africanism, and anti-colonial discourse, forging a literary and political bridge across the Black world. His contributions remain vital to global Black cultural history.

On May 4, 1994, after South Africa’s historic democratic elections, it was officially confirmed that Nelson Mandela and the African National Congress (ANC) had won, setting the stage for Mandela’s inauguration as South Africa’s first Black president on May 10. This moment was the culmination of decades of struggle against apartheid and a beacon for global human rights. Mandela’s leadership in promoting reconciliation over revenge inspired movements for racial and social justice around the world. May 4 symbolized hope, renewal, and the possibility of peaceful transformation.

On May 4, 1839, Prince Alemayehu, the son of Emperor Tewodros II of Ethiopia, was born — a figure whose life became a poignant symbol of colonial disruption. Following the British invasion of Ethiopia and the Battle of Magdala in 1868, Emperor Tewodros II died by suicide rather than be captured. Alemayehu, just a boy, was taken by British forces and brought to England under the supposed protection of Queen Victoria. Despite royal patronage, Prince Alemayehu lived a lonely and alienated life, separated from his people and homeland. He died at just 18 years old and was buried at Windsor Castle. To this day, Ethiopia has petitioned for the repatriation of his remains, which remains denied. Alemayehu’s story, largely overshadowed by larger imperial narratives, reflects early acts of cultural loss, displacement, and the personal cost of imperial conquest on African royal families.

Robert S. Abbott was founded The Chicago Defender with an initial investment of 25 cents. The Defender, which was once heralded as “The World’s Greatest Weekly”, soon became the most widely circulated black newspaper in the country, and made Abbott one of the first self-made millionaires of African American descent. Abbott also published a short-lived paper called Abbott’s Monthly.

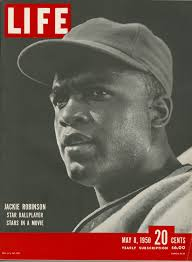

On May 5, 1975, Hank Aaron surpassed Babe Ruth’s long-standing record for career runs batted in (RBIs), marking another historic milestone in his legendary baseball career. Already known for breaking Ruth’s home run record the year prior, Aaron’s new RBI achievement solidified his legacy as one of the most prolific hitters in Major League Baseball history. He ultimately retired with 755 home runs and 2,297 RBIs, the latter of which remains the all-time record. Aaron was inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame on August 1, 1982. After retiring, he continued to influence the game through executive roles with the Atlanta Braves and has had stadiums, streets, and scholarships named in his honor.

On May 5, 1969, Moneta Sleet Jr. made history as the first African American to win a Pulitzer Prize for journalism. He earned the award for his deeply moving photograph of Coretta Scott King, widow of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., holding their young daughter Bernice at Dr. King’s funeral. The image, captured for Ebony magazine, conveyed the pain and resilience of a grieving family and a mourning nation. Sleet’s win was not only a personal triumph but also a groundbreaking moment for Black photojournalists in a field where African Americans were historically underrepresented.

Moneta Sleet Jr.’s career spanned decades, and he was known for documenting the civil rights movement, from the Montgomery Bus Boycott to the March on Washington. His Pulitzer win symbolized both progress and the power of Black media voices during the era of social change.

On May 5, 1865, Adam Clayton Powell Sr. was born in Franklin County, Virginia. The son of formerly enslaved parents, Powell would rise to become a prominent Baptist pastor and a towering figure in early 20th-century Black America. As senior pastor of the Abyssinian Baptist Church in Harlem from 1908 to 1936, Powell helped grow the congregation into one of the largest and most influential Black churches in the world. Under his leadership, the church expanded its role in community development, civil rights, and education. He laid the foundation for the political rise of his son, Adam Clayton Powell Jr., who became one of the most powerful Black Congressmen in U.S. history.

Mary Prince, born on May 5, 1809, in Bermuda, became the first Black woman to publish an autobiography in Britain, titled The History of Mary Prince (1831). Her firsthand account of the horrors of slavery stirred public emotion and galvanized the abolitionist movement. Prince’s story depicted brutal treatment, family separations, and the dehumanization endured under slavery. She bravely spoke at public meetings and petitioned Parliament, making her a crucial figure in the fight for emancipation in Britain and its colonies.

On May 5, 1821, the African Methodist Episcopal Zion (AME Zion) Church was officially incorporated in New York City. Known as the “Freedom Church,” it played a major role in the abolitionist movement and later the Civil Rights Movement. Leaders like Harriet Tubman and Frederick Douglass were members. The AME Zion Church provided spiritual strength and political advocacy, emphasizing education, civil rights, and racial uplift in African American communities.

On May 5, 1905, Bill “Bojangles” Robinson performed solo on the major vaudeville circuit for the first time, breaking racial barriers. His innovative tap dancing style captivated audiences and transformed American dance. Robinson’s career helped pave the way for future Black entertainers during a time of widespread segregation, and his success inspired the gradual integration of American entertainment venues.