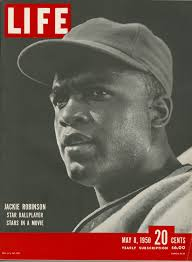

On May 10, 1950, baseball legend Jackie Robinson made history once again — this time off the field — by becoming the first African American to appear on the cover of Life magazine. In the publication’s 13-year history up to that point, no Black individual had ever graced its front page. Robinson’s appearance marked a significant cultural milestone, reflecting his role not only as a sports icon but also as a national figure of dignity and change. His presence on one of America’s most widely circulated magazines signaled a slow but meaningful shift in how Black excellence was represented in mainstream media.

On May 10, 1994, Nelson Rolihlahla Mandela was inaugurated as the first Black and democratically elected President of South Africa. Held at the Union Buildings in Pretoria, the ceremony marked the official end of apartheid and the beginning of a new era of multiracial democracy. More than 1,000 dignitaries from around the world, including U.S. Vice President Al Gore and Cuban leader Fidel Castro, were in attendance. Mandela’s inaugural speech emphasized unity, forgiveness, and the collective rebuilding of a “rainbow nation.” His election was the result of the first free and fair elections in the country’s history, with over 20 million people casting their votes. The moment symbolized not just political change, but global hope and the triumph of justice over oppression.

On May 10, 1963, Rev. Fred L. Shuttlesworth, a key leader in the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), announced a partial victory in the Birmingham Campaign. An agreement was reached between civil rights leaders and white business leaders to begin desegregating public facilities and to release jailed demonstrators. This compromise marked a turning point in one of the most influential civil rights movements of the 1960s. Though limited in scope, the agreement helped end weeks of nonviolent protests that had drawn national attention to racial injustice and police brutality in the Deep South. Shuttlesworth’s fearless activism, alongside Martin Luther King Jr. and others, helped lay the groundwork for the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

On May 10, 1962, Southern School News reported that 246,988 Black students—just 7.6% of the Black public school population—were attending integrated schools across 17 Southern and Border States and the District of Columbia. This report, released eight years after the landmark Brown v. Board of Education Supreme Court decision, highlighted the painfully slow pace of desegregation in American education. Despite federal mandates, widespread resistance from segregationist lawmakers and local communities continued to limit Black students’ access to equal educational opportunities. The publication’s data underscored the systemic barriers that persisted well into the 1960s and served as a sobering reminder that legal victories alone were not enough to dismantle institutional racism.

On May 10, 1951, civil rights attorney and educator Z. Alexander Looby was elected to the Nashville City Council, becoming one of the first Black council members in the city since Reconstruction. A fierce advocate for racial justice, Looby had already gained national attention for defending Black students in desegregation cases and for standing up to institutional racism in Tennessee. His election signaled a turning point in Southern politics and helped lay the groundwork for Nashville’s pivotal role in the Civil Rights Movement during the 1960s. Looby’s legacy lives on as a symbol of legal resistance, public service, and community empowerment.

On May 10, 1919, a violent race riot broke out in Charleston, South Carolina, when a confrontation between white U.S. Navy sailors and Black residents escalated into a night of chaos. The unrest resulted in the deaths of at least two Black men and injuries to dozens more. White mobs—many of them servicemen—looted Black businesses and attacked Black citizens with little intervention from local authorities. This event marked one of the early flashpoints of what would become known as the Red Summer of 1919, a period of widespread racial violence across the United States following World War I, driven by economic tensions, returning Black veterans demanding civil rights, and white backlash.

On May 10, 1837, Pinckney Benton Stewart (P.B.S.) Pinchback was born in Macon, Georgia. Born to a formerly enslaved woman and a wealthy white planter, Pinchback would go on to make American history during the Reconstruction Era. After the Civil War, he entered Louisiana politics and rose through the ranks as a fierce advocate for civil rights and education.

In 1872, Pinchback became lieutenant governor of Louisiana, and when the sitting governor was impeached, he stepped into the role. For 43 days, Pinchback served as acting governor, becoming the first African American to hold the office of governor in any U.S. state. He later helped establish Southern University and fought for the political representation of Black Americans during the volatile post-Civil War years.

On May 10, 1775, Black patriots stood alongside colonial militias in the first major offensive action of the American Revolutionary War—the capture of Fort Ticonderoga in New York. Led by Ethan Allen and the “Green Mountain Boys,” this surprise dawn attack secured a critical strategic point without bloodshed. Among the forces were free and enslaved Black men who risked their lives for a cause that would not yet recognize their full humanity. Their early participation in the war highlighted both the contradictions of liberty and the courage of those who demanded it from the start.

On May 10, 1652, John Johnson, a free Black man in colonial Virginia, was officially granted 550 acres of land in Northampton County. The land was awarded under the “headright” system, which offered land in exchange for transporting laborers—Johnson had imported eleven individuals. His acquisition of land during a time when Black freedom and property rights were rare in English colonies is a striking example of early Black agency in America’s colonial history. Johnson’s story reflects the complex realities of race, labor, and legal status in 17th-century Virginia—decades before slavery was fully codified in law.

On May 10, 1967, Carl B. Stokes won the Democratic primary for mayor of Cleveland, Ohio, placing him on the path to becoming the first African American mayor of a major U.S. city. His victory was a landmark moment in American political history, as it challenged longstanding racial barriers in urban leadership. Stokes, a former lawyer and state legislator, campaigned on issues of civil rights, police reform, and equitable economic development. His ability to build a multiracial coalition of support showcased a shifting political landscape during the Civil Rights era. Stokes went on to win the general election that November. His victory inspired a generation of Black political leaders across the country and proved that African Americans could lead in positions of high executive authority. His legacy remains tied to progress in urban governance and civil rights advocacy in American cities.

On May 10, 1963, in response to Ku Klux Klan intimidation and violence, the Deacons for Defense and Justice was founded in Jonesboro, Louisiana, by a group of Black men who had served in World War II and the Korean War. Tired of nonviolent protests being met with brutality, the Deacons armed themselves and patrolled Black neighborhoods to protect civil rights workers and local residents. Their presence was critical in places like Bogalusa and other parts of the South where local police refused to defend Black citizens. Though controversial among mainstream civil rights organizations, the Deacons played a significant role in advancing the movement by forcing federal intervention in areas plagued by racial terrorism. Their legacy influenced later Black self-defense ideologies, including the rise of the Black Panther Party. The group’s existence challenged the assumption that nonviolence was the only effective means of resistance in the fight for equality.

On May 10, 1877, the last federal troops withdrew from South Carolina and Louisiana, marking the end of Reconstruction. This date symbolizes the federal government’s retreat from protecting the rights of newly freed African Americans in the South. With the Compromise of 1877 resolved, President Rutherford B. Hayes ordered the military to cease its enforcement of Reconstruction-era policies. As a result, Southern white Democrats regained control of state governments and quickly instituted Jim Crow laws that disenfranchised and segregated Black citizens for nearly a century. For Black communities, May 10 represented the betrayal of the promises of the 13th, 14th, and 15th Amendments. The withdrawal allowed white supremacist groups to rise unchecked and ushered in an era of racial violence and systemic discrimination. The consequences of this decision reverberated well into the 20th century and remain a powerful lesson about the fragility of civil rights without federal enforcement.

Dr. Charles R. Drew, a medical pioneer who revolutionized blood storage and transfusion, died on May 10, 1950, in a car accident at the age of 45. Drew was the first African American to earn a Doctor of Medical Science degree from Columbia University and developed techniques that preserved blood plasma for longer periods. During World War II, he led efforts to collect and process blood for wounded soldiers, saving countless lives. Despite his brilliance, Drew resigned from the American Red Cross when it implemented a policy to segregate blood by race—a practice he vehemently opposed as unscientific and discriminatory. His death was widely mourned in the African American community, where he was hailed as a hero of both science and social justice. Drew’s legacy endures in medical schools, hospitals, and foundations named in his honor, and he remains an iconic figure in Black history and medicine.

On May 10, 1983, Harold Washington won the general election to become the first African American mayor of Chicago, following a contentious primary season and a highly racially charged campaign. Washington, a former congressman and lawyer, overcame deep resistance from the city’s political establishment and built a diverse coalition of Black, Latino, and progressive white voters. His victory signaled a major shift in Chicago politics, where the old machine had long dominated. As mayor, Washington focused on government reform, budget transparency, and minority inclusion in city contracts. His administration was marked by intense opposition from the city council, which was racially divided in what became known as “Council Wars.” Despite the challenges, his leadership opened doors for future Black politicians and inspired a broader movement for urban reform and equity in American cities. His death in office in 1987 was mourned nationally, and he remains a beloved figure in Chicago’s history.

On May 10, 1905, Anna Julia Cooper earned her Ph.D. from the University of Paris (Sorbonne), becoming one of the first African American women to receive a doctoral degree. Born into slavery in North Carolina in 1858, Cooper was a fierce advocate for the education of Black women and a prolific scholar. Her book A Voice from the South is considered one of the earliest texts of Black feminist thought. At the Sorbonne, her dissertation focused on French moral philosophy, and her academic success defied the gendered and racial barriers of her era. Cooper’s legacy as an educator and intellectual leader is vast—she served as president of Frelinghuysen University and influenced generations of students. Her contributions to philosophy, feminism, and Black education earned her the nickname “the Mother of Black Feminism.” Cooper lived to be 105, witnessing the Civil Rights Movement she helped make possible through decades of advocacy.

On May 10, 1996, former Congressman Kweisi Mfume was formally inaugurated as president and CEO of the NAACP, America’s oldest civil rights organization. At a time when the NAACP was struggling with financial instability and declining influence, Mfume revitalized its relevance. He focused on youth engagement, economic development, and expanding the organization’s digital and media reach. A former street hustler who turned his life around through education and activism, Mfume brought a compelling life story and political savvy to the role. His leadership emphasized coalition-building and advocacy on issues like racial profiling, education funding, and voting rights. Under Mfume, the NAACP regained some of its standing as a leading voice for African American issues during the post-Civil Rights era. His tenure marked a period of internal reform and renewed public visibility for the organization. Mfume would later return to politics, continuing a lifelong career dedicated to justice and equity.

Although James Baldwin’s birthday is not on May 10, this date is significant in his life because he graduated from Frederick Douglass Junior High School on May 10, 1938, a pivotal moment in his journey as a writer. Encouraged by his teachers and clergy, Baldwin developed his passion for literature during these years, setting him on a path to become one of America’s greatest writers. His works, including Go Tell It on the Mountain, The Fire Next Time, and Giovanni’s Room, challenged the intersections of race, sexuality, and class with unmatched intensity. His voice resonated through both literary and political spheres during the Civil Rights era. May 10, a simple school graduation day, reminds us that small milestones can signal the beginning of extraordinary lives. Baldwin’s early academic promise was a seed that would grow into a legacy of literary brilliance and social critique that endures to this day.

On May 10, 1974, Angela Davis resumed her academic career by accepting a teaching position at Claremont College, following years of political activism and legal battles. Davis had become internationally known after being placed on the FBI’s Most Wanted list and later acquitted of charges related to a 1970 courtroom incident. Her return to teaching symbolized both resilience and the importance of critical Black scholarship in higher education. Davis taught philosophy and women\’s studies, emphasizing issues like prison abolition, Black feminism, and Marxist theory. Her presence in academia marked a bold shift in who was seen as worthy to educate at the collegiate level. May 10 stands as a powerful reminder that radical thought and scholarship are not mutually exclusive. Davis’s career has since spanned decades, and she remains one of the most important public intellectuals in American history.

On May 10, 1967, Stokely Carmichael (later known as Kwame Ture), a Trinidadian-born civil rights activist, delivered a groundbreaking speech at Queen’s Hall in Port of Spain, Trinidad. It was the first time many in the Caribbean heard the term “Black Power” directly from one of its originators. Carmichael’s message challenged colonial legacies, economic inequality, and the psychological impacts of white supremacy. His call inspired a new generation of Caribbean youth to reject Eurocentric cultural values and reclaim their African heritage. This address was pivotal in igniting the Black Power Movement in Trinidad and Tobago, which would reach its height in the early 1970s. The Trinidadian government, viewing Carmichael as a radical threat, banned him shortly after the speech. Still, his words sparked political activism and pride throughout the Caribbean. This moment catalyzed nationalist movements that shifted regional discourse from assimilation to liberation and empowerment.

Born in St. Croix on May 10, 1881, Hubert Harrison became one of the most influential Black intellectuals of the early 20th century. Often called the “Father of Harlem Radicalism,” Harrison advocated for socialism, racial equality, and secularism. A fierce critic of Booker T. Washington and a predecessor to Marcus Garvey, he founded the Liberty League in 1917, calling for full civil rights, self-defense, and Black pride. Harrison edited several radical publications, including The Voice and The Negro World, and was a dynamic public speaker. His work emphasized class-consciousness while centering the unique oppression of Black people. Harrison’s ideas laid the intellectual foundation for later Harlem Renaissance thinkers and Black nationalist movements. Despite his brilliance and wide influence, he was marginalized in history due to his uncompromising stance against racial capitalism and colonialism. His birth on May 10 marks the emergence of one of the most radical Black voices in U.S. and Caribbean history.

On May 10, 1963, James Baldwin appeared in a televised discussion in London to speak about racism in America, coinciding with his growing popularity abroad. In the interview, Baldwin discussed the psychological toll of segregation, the hypocrisy of American democracy, and the moral imperative for white Americans to confront their complicity in systemic injustice. Baldwin’s eloquent, unflinching analysis captivated British audiences and elevated international awareness of the American civil rights struggle. His visibility in Europe allowed him to critique both American and European colonial mindsets, positioning Black liberation as a global moral issue. Baldwin’s appearance coincided with escalating racial violence in Birmingham, Alabama, giving his words haunting urgency. That May evening helped solidify Baldwin’s status as an international conscience and literary icon, using his platform to connect African American struggles with broader global movements for justice and human dignity.

On May 10, 1979, Black British and Caribbean activists staged coordinated protests in response to Margaret Thatcher’s harsh immigration rhetoric and policies. During her campaign and early days in office, Thatcher stoked xenophobic fears about Britain being “swamped” by immigrants. These remarks led to a surge in racial violence and emboldened far-right groups like the National Front. In response, community organizations such as the Black People’s Alliance and the Race Today Collective mobilized marches across London and Birmingham. May 10 marked one of the first major public protests against Thatcherism by Black communities. The demonstrations demanded racial equality, legal protections for immigrants, and an end to state racism. These actions helped shape the trajectory of Black British political consciousness, fostering solidarity and resistance that would later culminate in the Brixton Uprising of 1981. The protest signaled the beginning of a new era of militant anti-racist organizing in Britain.

On May 10, 1801, Haitian revolutionary leader Toussaint Louverture was deceitfully captured by French forces and deported to France. Invited under the guise of negotiation, Louverture was arrested by General Jean-Baptiste Brunet on orders from Napoleon Bonaparte. France feared Louverture’s growing power and Haiti’s independence momentum. Deported and imprisoned in Fort de Joux in the Jura Mountains, he died there in 1803 from neglect and exposure. His removal was part of France’s attempt to reassert control over Saint-Domingue and restore slavery. Despite this, Louverture’s revolutionary leadership had already laid the groundwork for Haitian independence in 1804. His betrayal on May 10 represents the enduring tension between colonial powers and Black autonomy. Louverture’s vision of racial equality, democratic governance, and economic independence would inspire anti-colonial movements across Africa and the Caribbean in centuries to come.

On May 10, 1903, the African Society was formally established in London to promote African culture, scholarship, and political thought. Founded by prominent Black scholars and allies—including Sylvester-Williams and Henry Sylvester-Williams—the society provided a platform for African and Caribbean voices at a time when British colonial narratives dominated. Its creation followed the 1900 Pan-African Conference and sought to challenge stereotypes while fostering unity among African diasporas. The African Society published the Journal of the African Society, which included essays, studies, and travel writings by African intellectuals. It became an early intellectual hub for Pan-Africanism and later evolved into the Royal African Society. May 10, 1903, thus marks the institutionalization of Black scholarly resistance within the British Empire and a foundational moment for global Black identity formation. The society helped shape early 20th-century discourse on African self-determination and post-colonial futures.

On May 10, 1981, the Ghanaian government under President Hilla Limann approved plans to construct a national mausoleum in honor of Kwame Nkrumah, Ghana’s first president and a towering Pan-African figure. Though overthrown in a 1966 coup and long demonized by military regimes, Nkrumah’s legacy experienced a revival in the early 1980s. The decision to build the mausoleum represented a national reassessment of his role in Ghana’s independence and African liberation movements. Completed in 1992, the Kwame Nkrumah Mausoleum became a major historical site and museum in Accra, preserving his writings, speeches, and symbolic artifacts. The May 10 approval signaled Ghana’s gradual embrace of Nkrumah’s vision for a unified, post-colonial Africa. His legacy continues to inspire Black liberation movements globally. The site stands as a monument not only to Nkrumah but to the broader struggle for African dignity and sovereignty.

On May 10, 1968, Tom Mboya, a prominent Kenyan politician and architect of the nation’s independence, narrowly escaped an assassination attempt in Nairobi. Mboya was a rising star and potential successor to President Jomo Kenyatta, known for his Pan-African ties and U.S.-backed Airlift Program that educated hundreds of East African students abroad. The attack was widely seen as politically motivated and highlighted growing ethnic and factional tensions within Kenya’s ruling elite. Though Mboya survived this attempt, he was fatally shot a year later, triggering nationwide unrest. The May 10 event is viewed as a precursor to Kenya’s descent into authoritarianism and political violence. Mboya’s vision of a progressive, meritocratic, and Pan-African Kenya was cut short, but his influence continues to be felt in Kenyan politics and educational reform.

On May 10, 1983, Prime Minister Maurice Bishop of Grenada delivered a fiery speech warning of increasing U.S. hostility toward his socialist government. Bishop, who came to power in 1979 through a bloodless revolution, had pursued policies of free healthcare, education, and agrarian reform with Cuban support. The Reagan administration viewed his government as a Marxist threat in the Western Hemisphere and began applying diplomatic and economic pressure. In his address, Bishop condemned what he called U.S. imperialism and vowed to defend Grenada’s sovereignty. Just five months later, he would be deposed and executed during a power struggle, leading to the U.S. invasion of Grenada in October 1983. May 10 stands as a stark reminder of the fragile path of post-colonial Black leadership in the face of global geopolitical forces. Bishop’s legacy remains contested but continues to inspire leftist and anti-colonial movements in the Caribbean and beyond.

On May 10, 1903, Ethiopia commemorated the decisive victory at the Battle of Adwa (1896) with the first National Unity Day celebration under Emperor Menelik II. While the battle itself is more widely known for halting Italian colonial ambitions, the 1903 Unity Day commemoration is far less discussed. This symbolic observance marked a pivotal effort to solidify Ethiopia’s diverse ethnic and cultural groups under a single national identity. Menelik used the event not only to honor the military triumph but also to strengthen ties between the Amhara, Oromo, Tigray, and other groups who had fought together. The ceremony included prayers, feasts, and the honoring of war heroes—many of whom were from underrepresented ethnic groups. Though this annual observance faded over time, it represented one of Africa’s earliest post-victory attempts at intentional nation-building and unity following successful resistance to European imperialism. Today, it\’s an overlooked but powerful testament to pan-Ethiopian solidarity.

© 2026 KnowThyHistory.com. Know Thy History